Promise and Performance: The Trials and Trails of India’s Industrialization

The 1960s and early 1970s in India are vital for understanding patterns of growth and structural tendencies of the national economy at large because in many ways they mark certain fundamental transitions that were, in fact, already observable by then. Agricultural growth rate fell sharply form 3.64 percent in the 50s to a mere 1.68 percent in the 60s and ‘non-foodgrain output growth was uniformly lower than foodgrain growth’. (Mohan Rao 1997: 7) Similarly, despite a fourfold increase in industrial production between 1950-1975, it can be seen that the average level of industrial production fell from 7.7 percent between 1951-65 to a sluggish 3.6 percent per annum during the decade 1965-75. (Nayyar, 1978) - Table 1. There was also a general slowdown in the heavy industry, with growth in metal production falling from a healthy 12.5 per cent per annum in the first period to a mere 2.5 per cent per annum in the second. (McCartney, 2009) Further, there have also been studies which pointed out the increased emergence of unutilized manufacturing capacity and a concomitant decline in the rate of industrial growth, as already noted. (KN Raj, 1976) Therefore, it is illuminating to see what this clear conjecture of declining growth rates in both industry and agriculture during the 60s imply in regards to the sustainability of the economic models of growth and productivity implemented primarily through the influential Second Plan.

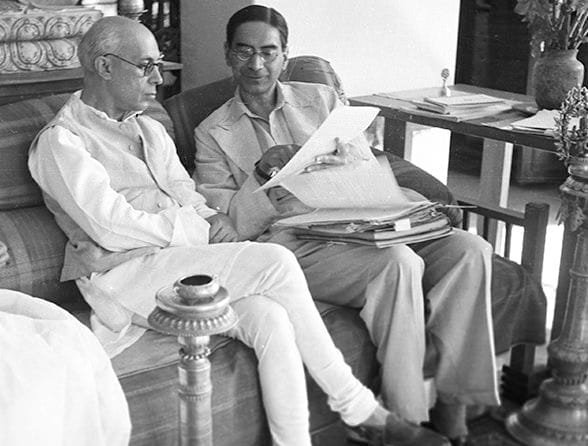

Nehru and Mahalanobis (Source)

In this essay, I argue that, although there had been exogenous factors such as poor harvests and loss of foreign demand and aid leading to foreign exchange shortages, the failure of the Mahalanobis strategy as evidenced by the economic slump from the mid-sixties, among other things, was caused by a much more fundamental failure at the heart of the strategy — namely, the incorrigible insistence on capital goods industrialization as being the primary means of national development within an overall context of income maldistribution, and demand deficiency. As India focused on real capital formation as the panacea for problems of employment and growth, the promise of perpetuation and sustainability of this model has been belied by the subsequent crises. In this context, I believe it is inevitable and imperative that one ask what it was that churned the “passions” of policy-makers and politicians to undertake heavy industrialization as the singular pathway to a certain ideal state of living. This is not to deny the diversification of economic structure, establishing of higher irrigation facilities and increased but inequitable potentials of self-sufficiency that this stress of large-scale manufacturing was able to accomplish, but it is to excavate and investigate the underlying ideologies, insecurities, inhibitions and formative powers that structured, sustained and directed the state-machinery and resource-allocative forces to take up this cause. In this essay, however, due to lack of space, I will focus only on aspects of economic promise and performance, nevertheless acknowledging the centrality of the historical question.

Table 1. (Nayyar, 1978)

Firstly, the interrelations between consumer goods, capital goods for producing capital goods, and capital goods for producing consumer goods was seen to be central to evaluating and achieving effective economic growth, as articulated in the Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy. (Chakravarty, 1987) The concomitant necessity here was also a need to increase the production of consumer goods using labour-intensive methods, (as opposed to direct capital investment by the government) and a general increase in employment in order to have the consumer demand proportionately expanding. Along with this, the overall success of the plan was also dependent on the inter-sectoral harmony. Any slowdown or insufficient performance in the agricultural sector would also lead to a dampening of the industrial growth. This would be the case if (i) agricultural supplies were limited because in India’s traditional industries such as that of jute, cotton, and sugar, were heavily dependent on agriculture for their raw material; (ii) if the ‘surplus of wage goods and investible resources are not forthcoming’, (Nayyar 1978: 5) then this could lead to slackening of output and inflationary situations, and finally, (iii) a general demand for the industrial goods will fall with rising food costs, severely hindering non-foodgrain consumption expenditure.

It should be noted here that the sources for financing and sustaining the conditions necessary for long-term productive growth was dependent as much on general public investment and the subsequent diversification of capital goods into manufactured goods, as it was on the ability of the government to procure resources for reinvestment by either taxing or incentivizing or directing the growing incomes of private players. The latter is important — for both social and political reasons as well - because a concentrated increase in the consumption of non-essentials and luxury goods at the cost of public investment and inequitable distribution of national income can only lead to an economy that is both unstable and unsustainable. Thus, it was assumed that the government would be able to socialize current income flows by financing investments through savings construed by private entities within an overall context of increased productivity of the public sector and community-held agricultural sector. Therefore, even if certain patterns of public investment can play an important role in Indian agriculture, as Chakravarty (1979) notes, ‘on demand side far more significant effects can be obtained in the long run sense by changes in agrarian relations.’ As a case for illustrating the inequitable demand, we can look at the year 1964-65, where it has been calculated that, in the rural sector, ‘the richest 10 per cent of the population was responsible for 32.2 per cent of the total consumption of industrial goods, whereas the poorest 50 per cent accounted for only 22 per cent of the total. Consumption inequalities were even more pronounced in the urban sector, where the top decile purchased 39.3 per cent of the industrial goods and the bottom five deciles absorbed just'19.9 per cent of the total.’ (Nayyar 1978: 7)

Here, it is pertinent to raise insights from Bagchi (1970) who identifies two critical problems with the strategy; namely, (i) ensuring balanced increase of supplies of different types of goods, and (ii) the inevitable discrepancies that arise between the distribution of demand and planned supplies of consumer goods. While the former may lead to loss of demand for capital goods if ‘capital-goods industries outpaces the planned rate of increase in the output of consumer-goods industries’, the latter can potentially exacerbate the problems of ‘inflation and evolution of the black market both in socialist and mixed economies’. At the core of his analysis is the plausible idea that the limited controlling powers and socio-political inhibitions of mixed economy governments cannot ensure cogency and cooperation with the more dominant economic forces, namely, the expenditure patterns of private sector. Therefore, it is important for us to acknowledge the presence of rural oligarchy in determining the course, feasibility and effectiveness of industrial growth (Mitra, 1977) because (i) it must be pointed out that export-led foreign-capital induced industrial growth cannot be sustainable as far as the domestic consumer demand is low due to unequal income distribution. This is because export-led policies will require alliances between ruling coalitions and urban industrial elite which, often, will have to come at the expense of the rural based rich peasantry. (ii) Consequently, a resolution to turn to external markets to replace the domestic demand bottleneck would entail policies that will ease licensing measures for industries and incentivizing MNCs (multinational corporations), cutting back on indirect taxes on luxury goods (because the majority demand is from urban and rural elite who indulge in such consumption), or cutting the level of income tax levied on the rich in order improve their scope for consumption and savings and so on — all of which would entail severe redirecting of resources and incentives for the welfare of the elite as opposed to more plausibly rural-poor-friendly policies such as fertilizer subsidies, public investment in irrigation and so on.

Given that, the social and political nature of elite demands should also be noted. They had to be concerned about protecting the structural benefits accruable by rigid maintenance of hierarchized divisions of land holdings, proprietary relations, tenurial conditions and caste privilege dynamics. One could claim that, in a supply constrained system, an increased role of public investment led growth could cure the demand deficiencies. But, as Chaudhuri (1998) notes, ‘even when public investment rises, what is crucial is the structure and character of investment’. If public investment is primarily utilised in accordance with political intents of decision-makers and the elite, then the issues will only be exacerbated.

Although, Nehruvian agrarian policies in the Second Plan did theoretically focus on achieving political power to the rural poor peasants while also improving agricultural productivity using labour-intensive methods, none of these ideals were substantiated or realized. Varshney (1998) insightfully shows how intra-Congress party struggles and discrepant realities on the ground, coupled with the increasingly failing overall agrarian productivity and loss of foreign exchange led to the eventual collapse of the institutional strategy employed by the Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy. One must note here that, along with the lack of local political support and mileage that was required to mobilize the resources for enabling the policy measures, the strategy made an oversight in at least two ways. Firstly, as Chakravarty (1987) notes, they treated the agrarian sector as a ‘bargain sector’ wherein it was optimistically believed that a slight capital investment and organizational restructuring through co-operatives, panchayats and indirect measures such as rural education would help increase the ever-required food supplies, thus balancing inter-sectoral costs, and cutting import costs. Thus, the government was confident enough to halve the total outlay in investment in agriculture and irrigation in the Second Plan, along with an absolute decline in irrigation expenditures.

But, more importantly, the assumption that industrial growth from well-achieving capital goods sector would rise in tandem with agrarian surplus proved to be a far cry. This was especially untenable given that there was no considerable plan delineating financial distributional mechanisms that must be at play in order to ensure equitable income distribution, even if there was, presumably, a formidable agrarian surplus. In other words, for equitable growth and increased productivity, there has to be implementational strategies concerning not only inter-sectoral relations, (questions dealing with price incentives, surplus labour, technocratic adjustments, movement of raw materials etc.) but also those of intra-agrarian forces (sub-regional variabilities, natural resource differentials, proprietary and holding relations, centre-state relations etc.) must be actively acknowledged. We see that in the Second Plan, the latter was meant to be achieved mostly through social restructuring and political programming as opposed to heavy economic investments. This proved futile in an overall scenario of a mixed economy and intra-party fractions where the government did not simply have the muscle to wrest its policy measures into fruition.

Consequently, it should be mentioned, thereby, that one of the main limitations of the Mahalanobis strategy was that it did not prioritize the ‘income distribution’ problem as it was centred on the issue of industrial productivity. This was so to such an extent that even the growth of consumption was schematized and imagined as being dependent on ‘prior increase in the capacity of the capital goods sector’. (Chakravarty 1987: 28) Thus, it is provocatively and profoundly insightful when Chakravarty compares this model as being a peculiar form of ‘trickle-down’ strategy because ‘it promised an improvement in the consumption level only as the end product of a process of accumulation’, even though it did not favour any high-income group as being necessary for accumulation. However, I think this opens up avenues to consider the three periods of planning as being a form of state-capitalism, as opposed to being strictly socialist. Additionally, it is pertinent we engage with this question about the nature of the state as well, because, as delineated by Byres (1997), theorising the nature of the post-colonial state as being either ‘instrumental/Hegelian’, ‘interventionist’, or ‘multi-class’ and so on has implications on how we approach planning, and in determining our priorities and possible blind-spots.

References:

Bagchi, Amiya. (1970) ‘Long-Term Constraints on India’s Industrial Growth, 1951-1968’ in Robinson, E.A.G. and Kidron, Michael (eds.) Economic Development in South Asia, London: McMillan and Co Ltd. pp. 170-193

Chakravarty, Sukhamoy. (1979) ‘On the Question of Home Market and Prospects of Indian Growth’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 14, No. 30/32. pp 1229-1242

Chakravarty, Sukhamoy. (1987) Development Planning: The Indian Experience, Oxford: Clarendon Press

Mohan Rao, J. (1997) ‘Agricultural Development under State Planning’ in Byres, J. Terence (ed.) The State, Development Planning and Liberalisation in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 127-172

McCartney, Matthew. (2009) India- the Political Economy of Growth, Stagnation and the State, 1951- 2007, London: Routledge

Nayyar, Deepak. (1978) ‘Industrial Development in India: Some Reflections on Growth and Stagnation’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 13, No. 31/33. pp. 1265-1278

Raj, KN. (1976) ‘Growth and Stagnation in Indian Industrial Development’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 11, No. 5/7. pp. 223-236

Varshney, Ashutosh. (1998) Democracy, Development and the Countryside: Urban-Rural Struggles in India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Nation Negated: Tagore, Periyar and Their Anti-Nationalism

In the June of 1916, under the Press Act of 1910, the government of British India passed orders against the founders and executive members of the Home Rule League and the Theosophist Society: Annie Besant, B.P. Wadia and George Arundale, and their associate newspaper New India. In order to quell their constant attacks against the British bureaucracy and their calls for Indian self-rule, the Act forbade them from participating in politics, whether in the form of writing or in speeches, and confined their movements to six specified locations that were not under the influence or reach of Madras City; their organization’s primary foothold. In the same week as this, Rabindranath Tagore, recently Nobel laureate and amassing global fame, arrived for the first time in the Japanese capital of Tokyo, where ‘some twenty thousand people turned out to receive him at the city’s central railway station’. Under a $12,000 contract with a speaking bureau in New York, Tagore was to deliver a series of lectures in the United States via a brief detour in Japan. It was these series of lectures that form the content matter of a slightly later publication in 1917 titled Nationalism, an important text for consideration in this essay. Finally, and importantly, in this very year of Nationalism’s publication, E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker makes an entry into the realm of nationalist politics by joining the Madras Presidency Association (MPA), a non-brahman enclave of the Indian National Congress.

Periyar and Ambedkar (Source)

What, one asks, do these three separate historical instances signify? In this essay, I argue that these seemingly disparate incidents, were, in fact, part of an ongoing ideological conjuncture of contending efforts to formulate differing ideas of the nation. By mainly focusing on the thought and activities of Tagore and Periyar, I will compare and show their critical visions and figurations of the idea of the nation. Broadly speaking, while Tagore represented nationalism mainly as a force of capitalist nation-state machinery, Periyar saw it as being congruent to Brahminical Hinduism. By doing so, they present to us highly critical visions of nationalism and, in turn, provide alternate modes of thinking about forms of belonging and resistance.

I will start off by showing that Tagore’s critical formulations of nationalism was part of post-World War I (post-WWI) forces of pan-Asian political cosmopolitanism and were enabled by his own socio-philosophical ideal of spiritualist humanism. Thus, owing to these Tagorean ideals, it is morally untenable to embolden nationalism, and hence it becomes necessary to negate and resist the idea of ‘nation’. In Periyar’s case, however, intersectional identities and intra-national forces of subordination demand that the idea of ‘nation’ be negated. Thus, a vector of subaltern identities of gender, caste, class, region and language, mobilised through the Self-Respect Movement, serve to defy the hegemonic utopia of nationalism. In the first section, I will also briefly discuss Annie Besant’s Home Rule League because its activities were part of the pan-Asian cosmopolitan moment that Tagore engages with, and they also form a prelude to the entry of Periyar’s Self-Respect movement. In the second section, I will discuss in greater detail Periyarite and Tagorean discourses against nationalism and conclude by discussing the alternatives they presented.

The Decade of 1916-26: Besant, Tagore and Periyar

As scholars such as Gauri Viswanathan, Erez Manela, and Mark Frost, among others have shown, during the end years of the WWI, what Frost calls the ‘cosmopolitan moment’ emerged. This roughly refers to the decade from 1916 to 1926, when, across the British territories, ‘elite expressions of nationalism merged with a new type of political cosmopolitanism’. Religious patriots, revivalists, and literary thinkers in Singapore, Ceylon and India — modernizing Buddhists, Confucian progressives and Theosophists, respectively - imagined and expressed ‘new visions of world order’. This order broadly meant a ‘reconstructed’ British empire, forming an imperial federation of countries, that was to bring about international brotherhood and permanent peace. Owing to the lack of space, and for our local purposes, I will only be focusing on the Indian scene at the moment that was predominantly occupied by the Annie Besant’s Home Rule League.

In early 1914, in the league’s other newspaper Commonweal, Besant wrote that ‘the term Empire has broadened to signify a unification of peoples under a single scheme of government which should allow its co-ordinated parts the widest possible freedom of autonomy’. Under this scheme of Home Rule League, the imperial federation, as presented in Besant’s Commonwealth of India Bill, involved the creation of a system of government that extended from village councils in rural areas and ward councils in municipal towns, to provincial parliaments and a national parliament that elects representatives to an imperial parliament. According to this plan, India’s national parliament would control its own army, navy and communications, though, as Frost notes, Besant later argued that India required the ‘continuance of the ‘imperial connection’ to preserve her from the threat of Russia’. Although, Besant’s ideas predate Wilson’s Fourteen Principles, Viswanathan and Frost, suggest that these ideas were formed under the influence of empire-builders like Joseph Chamberlain and Cecil Rhodes on the one hand, and Asian millenarians and reformist thinkers such as Anand Coomaraswamy, Dr. Lim Boon Keng, and Ponnambalam Arunachalam, on the other. Although, for the most part Besant received political support in Madras presidency and through adherents such as the “trinity” of Indian leaders Lal, Bal and Pal; her reputation was heavily compromised in 1919 when she took a stance that was interpreted as favouring General Dyers’ role in the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre and in her opposition to Gandhi’s Satyagraha. Unlike Besant, however, Tagore never invested the British Empire with his cosmopolitan hopes nor entertained the nationalist politics as the way to achieve his ideal of humanist universalism.

In Nationalism, he considers the idea of ‘nation’ as an extraneous category imposed upon Indian history due to its colonial encounter. He distinguishes between nation and society, what he calls samaj, and poses them almost as dialectical forces. The former serving a mechanical purpose, working through forces of commerce and military, deploying power (although, the political side of society does have this aspect, it is only for the sake of self-preservation, unlike the nation, which uses this to attain supremacy and so on). The samaj, however, is through which the attainment of human ideals is made possible and is an end in itself. The samaj, owing to the incursions of the West is under threat of being submitted to the forces of nationalism. The working principle of the former is competition between mechanically organized nations for the purposes of power, whereas the latter works through ideals of social cooperation and harmony, with those principles being an end in themselves.

In the former, self-interest reigns, and thereby breeds perpetually greed and jealousy for wealth and power limitlessly, while in the latter, it is the notion of ‘mutual self-surrender’ which sustains and enables a spirit of reconciliation. In the crucial sentence, he defines the colonial encounter as the ‘moral man, the complete man’ giving way, almost unknowingly, to the ‘political and the commercial man, to the man of limited purpose’. Significantly, Tagore understands 'nation' not as an identarian term, but as a transposable method of mechanical organization of power, an extraneous field of abstraction, that is always imposed (he even calls it an ‘applied science’) and thus as an anti-idealist force.

Thus, when we construe the Tagore’s impulse, the problem of nationalism cannot simply be posited within the field of political sociology because the ‘political’ is not the primary site of contestation in his emancipatory discourse. For Tagore, the ideal of freedom and universalist conviviality was, first and foremost, a preterpolitical task. It was to be attained and articulated through spiritualist humanism, the communal space of samaj, the aesthetic idealism of creative unity, and the ethics of heterological comity, among others. It is owing to this philosophical orientation that Tagore was able to pose the question that was new and, perhaps also, rather baffling or irksome to his contemporaries: what, his writings seem to ask, should the ideal of Indian freedom constitute of when it does not merely mean being untethered to the colonial yoke and establishing a modern nation? Thus, the further question is: what else is required of the ethical task of imagination and of living, when neither anti- colonial nationalism nor internationalist cosmopolitanism can bring upon the transcendent fellowship of humanity?

In this very decade, alongside Tagore, political developments in the Madras Presidency, form the preconditions for the emergence of Periyar. As Barnett and Irschick show, in the early-twentieth century, a nexus between Home Rule League, the Congress and the Brahmin community was felt very strongly by the rural, land-owning non-brahmin jatis. Along with the fact that major players in the League and Congress were mostly Brahmins, their predominance in administrative jobs and university-level education was observed and protested. Thus, in response to the belief that Home Rule merely meant Brahmin rule, Justice Party was established in order to advocate against Home Rule and prioritize social reform and non-Brahmin demands over the Congress-League politics. It was in this context that Periyar joined MPA, and in later stages, even radicalized further, as I will show in the next section.

E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker (1879-1973), known to his followers as Thanthai Periyar; the Great Man — a self-conscious dig at his nemesis Gandhi, the Great Soul - was born in the trading town of Erode in Tamil Nadu. His father, Venkatappa Naicker, worked as a stone mason and coolie, and he lived in great poverty for the first half of his life until he earned his way upward through trading. It was in this now-wealthy household, infused by Brahminical religiosity, that Periyar was born into. Periyar recalls the donative thrust of his wealthy mid-caste family where charities to temples, cow-gifting to Brahmins and patronaging of wandering Hindu monks who debated religion in his house was a common feature in his early life. Periyar himself, at the age of twenty-five, left home as an itinerant monk, along with two other Brahmins, travelling to North India. He travelled to Puri, Calcutta, and Benares where he worked in a Hindu ashram, translating religious sermons of his Brahmin compatriots and collecting leaves and materials for conducting the daily puja. After two years of this sadhu lifestyle — during which, he later said, he witnessed firsthand the corrupt practices of the Brahminical fold - he was taken back to Erode by his father.

The Next Decade, 1926-36: Tagore and Self-Respect Movement

The very Periyar, who wandered the stretches of the Indian subcontinent as a wandering sadhu, translating religious sermons; around three decades later would set sail on the French ship, Amboise, from Madras that would take him touring the Soviet Union and other European countries. In this Soviet tour of 1931, however, he was translating into Tamil the Communist Manifesto and was attending the May Day Parade at the Lenin Mausoleum at the Red Square, meeting with atheist-rationalist societies such as League of the Militant Godless and German International Freethinkers’ Association. He was so inspired by the Soviet power —the hydroelectric stations of Dneprostroi and Zaporizhia, Avtomobilnoe Moskovskoe Obshchestvo, the efforts of Profintern offices (Red International of Labor Unions), and its resilience during the era of Great Depression and so on - that he even named the children of a leading Dravidian intellectual ‘Russia’ and ‘Moscow’. Similarly, Tagore, who travelled to the Soviet in the same ship the previous year, also spoke highly of the Soviet spirit for having ‘raised the seat of power for the dispossessed’. He was particularly admiring of the Soviet education system, which he discusses in his fifth and seventh letter that he wrote from Berlin. He was particularly struck by the active participation and visiting of the working-class members and craftsmen in art exhibitions that were previously only the reserve of the upper-class aristocrats and art connoisseurs. In the seventh letter, he even discusses the Soviet use of the museum as a pedagogic site. Although he identifies the repressive dimension of Soviet’s propogandist education, Tagore, however, hoped that this spread of education and the consequent banishment of illiteracy, could serve to further democratize the state in the future. The Soviet experiment was important for Tagore because it served as a model for the Indian nation that was poor, agricultural and mostly illiterate, just like Russia before the Revolution of 1917.

Tagore, however, had his reservations against many Soviet characteristics, one of which is chiefly pertinent for our purposes, namely his stressing of the links between nationalism and violence. In an interview he gave to the newspaper Izvestia, he advised the Soviet government to ‘never create a force of violence which will go on weaving an interminablechain of violence and cruelty’. He mentioned that the ‘[F]reedom of mind is needed for the reception of truth; and terror hopelessly kills it’. However, as it was later made evident in Moscow show trials and the Stalinist purges, this warning seems prescient. The powers and needs of nationalism, by the suppression of the individual and by the coercive hegemonizing of cultures, necessitates the use of violence. According to Tagore, this was an interminable and originary link between nationalism and violence.

This link between nationalism and violence gets articulated in Periyar through his emphasis on the centrality of Brahminism. It was also during the early- to mid-20s that Periyar rejected Gandhian Congress, as he became increasingly convinced that Gandhi’s politics of negotiation and accommodation with Brahmins was not radical and just enough to realize his ideals. Periyar believed that Gandhi sought to “attack” Brahminism while upholding varnashrama dharma — a self-contradictory move - as became clear in Gandhi’s responses to Vaikkom Satyagraha and temple-entry protests. Thereafter, according to Periyar, the ideology and function of the ‘nation’ as a concept was homologous to Brahminical Hinduism both in terms of its networks and ideals. Here, most significantly, we need to note that ‘Brahminical Hinduism’, in Periyar’s usage, was an all-encompassing term that included and referred to Aryan and North Indian subordination, Hindi-Sanskrit hegemony, patriarchal systems of power, upper class domination and even the institute of Congress. Thus, his Self-Respect Movement, which sought to eradicate and oppose Brahminical Hinduism/Nationalism, involved issues that cut across all the inferiorized, subaltern identities of caste, gender, class, language and region. There are two main things to note here about this Periyarite conceptualization of Brahminical Hinduism/Nationalism.

Firstly, by making ‘nationalism’ and ‘Brahminism’ continuous, homological and transitive entities; Periyar was able to emphasize and attack the very core upon which these power structures are predicated. Namely, their irrational, constructive and classificatory function. The most astounding and “scandalous” aspect of Periyar’s radicalism springs from this very recognition of its core function. To further substantialize this point, we can consider his 1955 declaration, when he advocated for the public burning of the Indian National Flag. Here, he invokes Thiruppur Kumaran, a Gandhian nationalist, who died in January 1932 because of brutal police attacks when he refused to let go of the British-banned Indian National Flag. Periyar said:

“Why shouldn’t we burn [the Indian National] flag? Is it because Thiruppur Kumaran saved it? Is the cloth so soiled that it will not burn? All that is needed is little more kerosene and it will burn. Or is it made of some fire-proof cloth? A lump of clay becomes Vinayaga. Isn’t it the same story when a cubit length of cloth becomes the flag? We have proved that Vinayaga had the same worth as a lump of clay. Similarly, we will prove that your flag has the same value as a cubit length of rag.”

Here, we can observe a series of remarkable reinterpretations being undertaken, all made possible owing to the Periyarite recognition mentioned above. The first thing to note is that Kumaran, in Periyar’s reading, cannot simply be glorified and subsumed within the nationalist discourse as a martyr. In fact, upholding Kumaran as a martyr would amount to condoning the very evil of nationalism. According to Periyarite discourse, Kumaran is more a ‘victim’ of nationalism than he is a heroic martyr. This is because Kumaran, an exemplar of the nationalist public, fails to see the constructive nature of nationalism and its deep linkages with the Brahminic discourse. The passionate euphoria, the sense of belonging, the sacrificial compulsion, and the ethics of self-annihilating reverence inspired by the nationalist symbology all serve to dehumanise and deify the nationalist subject. It is this dehumanisation that Periyar finds to be irrational. This ‘irrationality’ can only be produced and sustained because of the constructive character of these symbols, affects and ideologies. Moreover, Periyar even identifies a congruence between the Brahminic Vinayaka and the National Flag, thus highlighting their homology. In many ways, he is also hinting at the theological foundations predicated in both cases where the ideals of devotion and deification, surrender and sacrifice, reverence and repression are all active. Given these forms and formulations, Periyar’s response is to aver the pragmatic materiality of things. The flag and the idol are merely objects that are instrumentalised and propagated as more worthy than a human life. Thus, if this ‘objective’ element is recognised and the schism between the symbol and substance, the material and the immaterial, the real and the reinforced is identified, one can see things more clearly. Thus, for Periyar, emancipation and democracy can only be achieved through an undertaking of rationalist inquiry. Rationalist public inquiry lays bare things and events providing clarity and truth. More importantly, it emancipates the nationalist-subject from the shackles of Nationalism/Brahminism by way of humanism. Similarly, it is owing to this disenchanted, rationalist framing that he was able to describe the idol in Vaikkom temple in 1924 as ‘a mere piece of stone fit only to wash dirty linen with’. On the same note, he criticized the Hindu public saying that ‘[H]ad it not been for the rationalist urge of the modern days, the milestones on the highways would have been converted into gods. It does not take much time for a Hindu to stand a mortar stone in the house and convert it into a great god by smearing red and yellow powders on it’. Therefore, we see that the religiosity of nationalism and Brahminism was opposed to the virtues of rationality. As M.S.S. Pandian summarily notes, ‘self-willed reason alone could restore the real worth of those enslaved by religion’ and the Self-Respect Movement strived to do the same.

Self-Respect Movement (Source)

Secondly, Periyarite notion of ‘Brahminical Hinduism/Nationalism’ was useful as a political strategy for public mobilization and the ease of ideological communication. By pointing out to the inextricable link between the two conceptual entities, Self-Respect Movement was able to consistently mobilize and address the large subaltern non-brahmin public. Thus, a critique of Nationalism as Brahminical Hinduism enabled Periyar to consider and address issues emerging across a vector of identities, such as gender, caste, class and language. We can start by looking at the language question in Periyarite discourse, and specifically, how it was developed during the Anti-Hindi agitations of the 1930s. The agitations mainly erupted as a response to the C. Rajagopalachari - led Tamil Nadu Congress government’s decision tointroduce Hindi in schools. The anti-Hindi agitations, as commonly misconceived, were not merely a product of jingoistic Tamil chauvinism or a romanticized idea of Tamil purity and its ancientness. In fact, Periyar’s comments on the issue are instructive in this regard. He outlined his position as follows:

“I do not have any attachment to the Tamil language for the reason that it is my mother tongue or the tongue of the nation. I am not attached to it for the reason that it is a separate language, ancient language, language spoken by Shiva or language created by Agastya. I do not have attachment for anything in itself. That will be foolish attachment, foolish adulation. I may have attachment for something for its qualities and the gains such qualities will result in. I do not praise something because it is my language, my nation, my religion . . . If I think my nation is unhelpful for my ideal and could not [also] be made helpful, I will abandon it immediately. Likewise, if I think my language will not benefit my ideals or [will not help] my people to progress [and] live in honour, I will abandon it.”

It was through this logic that the Self-Respect Movement evaluated English, Tamil and Sanskrit. Sanskrit, with its strong links to the Pundits and their cultural superiority, was always rejected by the movement as a language that denied equality and dignity to the subaltern classes that it forcefully excluded. English, on the other hand, as Pandian notes, was regarded ‘as a language of modernity rather than as a language of colonial governance’. Although, the movement recognised that English was central to the Brahminical acquisition of cultural capital and in their usurpation of bureaucratic power, it reinterpreted the role of English. It was understood that English could be used as an alternative space to carry out the critique of the extant power relations, and through it access the global ideas of freedom and liberation. Therefore, Periyar says that ‘it is no exaggeration to say that it is the knowledge of English which has kindled the spirit of freedom in our people who have been cherishing enslaved lives. It is English which gave us the wisdom to reject monarchy and to desire a republic; to reject Sanathana Dharma and desire socialism. It gave us the knowledge that men and women are equal’. In fact, this attitude is highly consonant with Tagore’s reservations against Gandhi’s actions during the Non-Cooperation movement. Gandhi, in a long essay called ‘Evil Wrought by English Medium’ censured figures such as Rammohun Roy and Tilak for using English as their primary means of expression and ideation. He also argued against the ‘superstition’ that English was necessary for ‘imbibing the ideas of liberty and developing accuracy of thought’. Just as Periyar, Tagore also considered this Gandhian attitude to be flawed and dangerous. While Gandhi identifies the imposition of a foreign language as damaging, Tagore and Periyar argue that it was precisely an interaction with these other languages that gave rise to wider comprehensiveness and increased cultural exposure. Thus, Tagore writes that Rammohun Roy, due to his knowledge of other languages, was, in fact, able to have ‘the comprehensiveness of mind to be able to realize the fundamental unity of spirit in the Hindu, Muhammadan and Christian cultures. Therefore, he represented India in the fulness of truth, and this truth is based, not upon rejection, but on perfect comprehension. Rammohun Roy could be perfectly natural in his acceptance of the West, not only because his education had been perfectly Eastern, — he had the full inheritance of the Indian wisdom. He was never a schoolboy of the West, and therefore he had the dignity to be the friend of the West’. This position regarding English highlights a very important and common feature between Tagore and Periyar. Unlike Gandhi and their other contemporaries, Tagore and Periyar did not automatically accept the intrinsic validity of the national space which was required in order to sustain the binaries of Foreign/Domestic, Colonial/Colonised and English/Indian and so on. This was not because they were turning a blind eye to the brutal reality of colonialism. Instead, they identified that these binaried categories cannot be fully essentialised and that each category was internally differentiated. Moreover, they were interested in establishing and enabling the interface between these categories and emphasising their interrelation. Thus, it would be a mistake to read their efforts to collapse this dichotomous view as a form of ambivalent support for the British colonialism.

Given this, the role of Tamil has to be further explored in anti-Hindi agitations within the Self-Respect Movement. Unlike the orthodox Tamil Smarthas, Vaishnavites and Shaivites, Self-Respect Movement discourse did not posit an easy, taken-for-granted opposition between Tamil and Sanskrit. Instead, it was understood that, although it was better than Sanskrit, Tamil also had ingrained many forms of disempowerment and exclusionary vocabulary that had to be refashioned in order to deem it progressive and democratic. The main cultural forms that inhibited Tamil were seen as religion and gender. Therefore, leaders such as Kuthoosi Guruswamy and Periyar criticized the canonisation of ancient Tamil texts such as Thirukurral and Silapathikaram because they were seen as promoting gender inequality and upholding patriarchal structures. On a similar note, they criticized the promotion of Tamil through Puranic and epic Kavya literature alone and thereby sought to ‘de-sacralise’ the language. This was done by campaigning against singing Saivite hymns inconferences, teaching religious texts as part of Tamil language courses, and including invocations of gods in school textbooks. Thus, this auto-critique of Tamil enabled the Self- Respect movement to mobilise and garner support of women and lower-caste groups as well.

In this connection, the question of the relationship between gender and Brahminical nationalism within the Self-Respect Movement has also to be emphasised.

The most important way in which Periyar opposed the patriarchal foundations of Brahminical nationalism was by attacking the institutions of marriage and family. By insisting that marriage was merely a way of enslaving women and turning her into private property, he initially campaigned for complete abolition of marriage itself. However, during the Self-Respect Movement, he advocated a form of marriage that ‘transcended the traditional and socially-accepted norms for women’. In this new form of marriage, all rituals associated with traditional marriage had to be abandoned, including the tying of thali which he regarded as a symbol of male subjugation. These marriages were conducted without the presence of Brahmin priests and were scheduled during times that were traditionally considered as inauspicious, such as during Rahu Kalam or midnight. Apart from these, he opposed arranged marriages and advocated men and women to choose their own partners. And as aforementioned, he also sought to reform the patriarchal heritage of Tamil language itself. For this reason, he introduced such neologisms into Tamil such as vidavan (widower) and vyabicharan (male prostitute), which had not existed before. Along with these measures, the Self-Respect Movement also ensured that a substantial women presence be maintained in public conferences, by creating a separate women’s conference and by ensuring women preside over and fairly participate in general conferences. It was therefore that feminist figures such as R. Annapurani, T.S. Kunchidam and S. Neelavathi, among others were prominent during the movement.

Thus, we see that representatives of identical categories encompassing gender, caste and language were able to articulate and refashion their political will and reason within the Periyarite discourse. The realist and rationalist thrust of Periyarite politics deemed impossible the hegemonic and all-encompassing utopia of nationalism by stressing the existence of factional divisions, and intra-categorical differences. Therefore, nationalism was understood not as an antidote to these various vexing problems, but as an ideological and socio-cultural system that actively sought to erase or underplay these issues. Tagore, on the other hand, criticized the extraneity and violence of nationalist machinery, as that which diminishes humanity’s ability and proclivity to commingle, and establish peace and internationalist fellowship. In doing so, and owing to their critical prescience, courageous eloquence, and unwavering efforts for collective betterment; the antinomies and anxieties of the contemporary moment can be better addressed.

References:

Anandhi S, ‘Women’s question in the Dravidian Movement, 1925-1948’, Social Scientist, 19 (1991), 24-41.

Barnett, Marguerite Ross, The Politics of Cultural Nationalism in South India, (New York: Princeton University Press, 1975)

Besant, Annie, ‘On the watchtower’, The Theosophist, 36.2 (1914), 97–103 (p. 99).

Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi, ‘Rethinking Tagore on the Antinomies of Nationalism’, in Tagore and Nationalism, edited by K. Tuteja and Kaustab Chakraborty, (Shimla: Springer Publications, 2017)

Bhattacharjee, Manash, “Tagore’s Prophetic Vision in 'Letters from Russia'”, The Wire, September 11, 2020, https://thewire.in/history/rabindranath-tagore-letters-from-russia-soviet- union.

Chidamparanar, Sami, in Leader of Tamils: Biography of Periyar EVR (Madras: Periyar Self- Respect Propaganda Institute, 1983)

Dirks, Nicholas, Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the making of modern India, (New York: Princeton University Publication, 2001)

EV Ramaswamy, in Thoughts of Periyar, edited by V. Anaimuthu (Tiruchinapalli: Thinker’s Forum, 1974).

Frost, Mike, ‘Asia’s maritime networks and the colonial public sphere’, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 6.2 (2004), 63–94.

----------, ‘Beyond the limits of nation and geography: Rabindranath Tagore and the cosmopolitan moment, 1916-1920’, The SAGE Journal of Cultural Dynamics, 24.2 (2012), 143-158.

Gandhi, Mohandas, and Ramachandra Prabhu, Evil Wrought by English Medium, (Ahmedabad: Navjivan Publishing House, 1958)

Guha, Ramchandra, ‘Travelling with Tagore’, Penguin Classics, (2012), 1-51.

Irschick, Eugene F, Politics and Social Conflict in South India: Tamil Separatism and Non- Brahmin Movement, 1916-1929, (Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969)

Manela, Erez, The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism, (New York: Oxford University Publications, 2007).

Pandian, MSS, Brahmin and Non-Brahmin: Genealogies of the Tamil Political Present, (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2007)

--------, 'Denationalising' the Past: 'Nation' in E V Ramasamy's Political Discourse’, Economic and Political Weekly, 28.42 (1993), 2282-2287.

---------, ‘Nation Impossible’, Economic and Political Weekly, 44.10 (2009), 65-69. Periyar, Thanthai, Why were women enslaved?, edited by K. Veeramani, (Madras: Periyar Self-Respect Propaganda Institute, 2020)

Sen, Krishna, ‘1910 and the Evolution of Rabindranath Tagore’s Vernacular Nationalism’, in Tagore and Nationalism, edited by K. Tuteja and Kaustab Chakraborty, (Shimla: Springer Publications, 2017)

Tagore, Rabindranath, in Truth Called Them Differently: Gandhi-Tagore Controversy, edited by Prabhu and Kelekar, (Ahmadabad: Navjivan Publishing House, 1961)

-----------, Letters from Russia, (Calcutta: Viswa-Bharati Publications, 1960)

-----------, Nationalism, (Delhi: Penguin Classics, 2012)

-----------, Creative Unity, (London: McMillan and Co., 1922)

Venkatachalapathy, AR, “Periyar’s Tryst with Socialism”, The Hindu, September 18, 2017,https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/periyars-tryst-with-socialism/article19704347.ece.

Viswanathan, Gauri, ‘Ireland, India and the poetics of internationalism’, Journal of World History, 15.1 (2004), 7-30.

The Gradual Origins of Indo-Lanka Liberalization Reforms

When dealing with the question of structural reforms in South Asia, there are two interesting issues that arise, especially in the case of India and Sri Lanka. Firstly, we notice that the impact that the reforms have had in India were quite negligible in improving the rates of growth in manufacturing industry, total factor productivity rates, aggregate economic growth, employment rates in the manufacturing sector and of capital formation. Many scholars argue that in fact a much larger shift in the trend of growth rates can be observed during the 80s in India, that is, a decade before the reforms were carried out most forcefully. Conversely, in Sri Lanka, post-1977 reforms led to a burst of short-term economic growth with a jump in GDP rates within four to five years. Secondly, we see that in the case of both Sri Lanka and India, this new economic vision of reforms was as much a product of immediate and internal economic crises as it was a political project to redefine new alliances and state priorities.

Dr. Manmohan Singh, then Finance Minister of India, officially announcing the liberalization reforms in 1991. (Source)

In this essay, I argue that there are, broadly, two factors can be identified that explain the gradual structural transformation of these economies: (i) firstly, the growing dissatisfaction with the state-led planning economy, which which has arisen not only because of the states’ underperformance over the decades, but also because of a general ideological shift in understanding the role and the nature of the state; (ii) secondly, the gradual culmination of internal crises, coincidentally with various exogenous shocks or externally dependent or determining conditionalities. It is also worth noting here that, additionally and perhaps more interestingly — and this is to some extent a partial product of the two factors mentioned above — a peculiar link started to be drawn between socio-ethnic conflicts and the advancement of a liberalized economy, which became an essential part of the discourse of nationalism and sovereignty in general. In other words, the third factor underscores the attempts of these states to produce ‘economistic’ discourses in order to either make sense of or justify concomitant incidences of ethnic violence seen at the time.

Given this, there were generally two camps of thought which actively debated these issues. One, largely critical of the reforms, emphasized that the supposed failures of state-led development were not as acute as neoliberal writers were claiming, and that therefore, it was important to trace the political economy changes, i.e.; the role of bureaucratic-businessmen alliances, or the shifting governmental priorities pushed forth by, and in favour of, elite interests in order to understand the emergence of reforms. Then there were those who actively advocated reforms, pointing out to the stifling measures of state-led planning economy, which was unable to unleash the entrepreneurial spirits of the nation, or improve the overall economic efficiency, and therefore could not integrate into the global market by attracting foreign capital and increasing incentives for domestic private investment. There are, needless to say, considerable variations within each of these camps which I will try to present as well.

The underlying argument here is that a failure of the socialist developmental schemes led to a gradual but partial reversal in the states’ responses to the constraints present at the time of reforms which motivated them to liberalize. Here, I use the word ‘partial’ in a double sense: in lieu of Corbridge (2000), as being partial or favourable to elite interests, and secondly, as ‘incomplete’, in the sense that there was never a complete or absolute withdrawal of the state from the economic apparatus.

Two Models of Divergence

There is an interesting divergence in the development models of India and Sri Lanka before they took on the reforms, which evinces that diversity in approaches to state intervention exists even within development states. While India predominantly focused on heavy industrialization and capital formation as a way to alleviate poverty, by contrast Sri Lanka prioritized public spending on social welfare mechanisms and various subsidizing policies. Over the long-run, while failure to (i) mobilize domestic resources, (ii) direct and sustain savings into productive investment, (iii) to create rural demand and increase agrarian productivity, and (iv) persistent levels of poverty, unemployment and under capacity utilization etc. led to an economic slump in India in the 70s, in the case of Sri Lanka, we see that an overdependence on plantation-led exports revenue could not sustain the pervasive expansion of the public sector in regulation, production and welfare which eventually led to a deteriorating exchange position. (Herring, 1987)

In a sense, these long-term experiences with state-led development that either underperformed (as was the case in 70s India) or pushed the economy to the brink (Sri Lanka in mid-70s) could be seen as feasible economic explanations that led the states’ gradual embrace to a more market-led liberalization economy. In India, a visible shift toward furtherliberalization was already discernible in the 80s before it achieved a state of ‘reforms proper’ in the early 90s. Gandhi’s regime, which returned to power in the 1980 elections banking on the socialist rhetoric of ‘garibi hatao’, could already be seen to be making policies in favour of the indigenous businessmen and industrialists. Also, these tendencies were relatively heightened in the succeeding Rajiv Gandhi regime. A spate of industry deregularization policies were introduced along with the lifting of trade restrictions. In the early 80s, ‘thirty-two groups of industries were delicensed without any investment limit, and this was followed by removal of licensing requirements for all industries except for those on a small negative list, subject to investment and location limitations.’ (Ghosh, 1998) Similarly, in 1985, the coming of Open General License increased the list of exportable items and exporters were now able to access imported inputs at world prices. However, it should be noted that these changes were occurring alongside an increased cutting of subsidies in the public distribution system and dissolution of the Food for Work program in 1982. (Kohli, 2006) Thus, we observe here not only the commencing of these explicit liberalization- friendly policies, but an active emergence of a renewed economic propensity favouring newer priorities. As Kohli (2006) notes, the state was now increasingly seeing itself as a mediator in coalition with big businessmen to achieve economic growth as opposed to the earlier idea of planning economy. Thus, these lucid remarks by Ghosh captures the changing dynamics of the 80s economy:

While the economic expansion that occurred was dominated by the straightforward Keynesian stimulus of large government deficits, the role of planned investments in this process was very limited. Indeed, it was government expenditure that led to economic expansion which was finally reflected in an expenditure-led import-dependent middle class consumption boom. The effective irrelevance of planning meant that growth patterns were determined much more by market processes than by state direction. (Ghosh, 1998, pp. 321)

However, there are, in my view, some certain qualifications that have to be made here. Although, state direction did decrease, as Ghosh points out, this is not to say that India, even in the early 90s, was able to, or willing to, totally ‘withdraw from the economy’, whatever that may entail. Instead, we see that, as in the case of Sri Lanka, undertaking an economic logic of liberalization essentially means a shifting of governmental priorities and a fundamental reshaping of the nature of the state, rather than, what Herring calls, ‘wholesale privatization campaign’. (Herring, 1987)

The Partiality of Reforms

While in India the gradual tilting was discernible through various policies employed in the 80s, in Sri Lanka this shift was most pronounced in the 1971 austerity budget. But, as in the case of India, the role of the state was not completely minimized but only changed. Now, the states would play a lesser role in regulation, commerce, and production. These were discernible by an increased change in composition of overall investment with private investment crossing the levels of public investment in both states and the many deregulation procedures undertaken. However, the state had still to play an active role in developing public infrastructure, which was thought to create the initial conditions necessary to attract and sustain private investment. One subtle irony here was that while the reformist philosophy and the pro-business economy, in practice, emphasized banking on already established private actors, the theoretical rhetoric was that the capital would actually flow into capital-scarce areas and improve labour-intensive growth, thus fuelling employment. But the problem with this was twofold. Firstly, these expectations did not actually materialize as can be construed by the largely unchanging industrial growth rates and employment rates. Secondly, it paved the way for eliminating the existing structures of welfare provisioning mechanisms. Thus, instead of strengthening these measures, which had been instrumental in sustaining formidable rates of human development in these countries, governments took an anti-labour and anti-poor turn.

It should be noted here that these changeshave taken place within an overall context of partiality. Thus, for example, the passing of Essential Public Service Act in 1979 in Sri Lanka gave the state the powers to outlaw trade union activities across the states. Likewise, the Tamil rural poor had to face unfavourable conditions as, for instance, when the imports of agricultural commodities such as grapes, chilis and onions were liberalized in Jaffna, while the paddy and potato crops, which were mostly grown by the Sinhalese farmers, were protected. Even the public investment programs, which were largely funded by external monetary agencies and banks such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, as well as through foreign aid, have led to discriminatory projects. The Mahaweli Development Project was, for instance, seen as a matter of nationalist pride, while the Tamils were protesting against it because the project was deemed to encroach lands that traditionally belonged to them. (Dunham and Jayasuriya, 2001) Similarly, the insistence of the pro-reform Jayawardane government in 1977 on reducing food subsidies was also not a product of economic rationalizing. There was no established evidence or justification to suggest that the closed economy’s trade policies or stunted growth rates was a direct result of public expenditure on food subsidies. (Herring, 1987) In fact, as Dunham and Jayasuriya (2001) pointed out, the annual subsidies on Air Lanka was exceeding domestic expenditure on public transport and sometimes also on food subsidies. Here we can note that the reforms were driven not only by economic considerations, but also by broader socio-ethnic and ideological leanings.

Sri Lanka 1977 riots, the year of liberalization reforms. Source

Just as in Sri Lanka, we can observe a similar bias in Indian reforms. However, it should be noted here that these reforms were not singularly beneficial to the elite classes and favoured majoritarian ethnicities. It is true that there was a short-term growth that was made possible following the 1977 reforms in Sri Lanka and, furthermore, the government was able to deal effectively with the fiscal deficit crisis after the reforms. However, the question of the sustainability and bias of these reforms has to be acknowledged. Thus, the continued failure of the Indian state to invest in education and health infrastructure contributes to the violent inequalities in enabling access to accruing social capital for the lower classes and depressed castes. Additionally, the determining importance of possessing certain initial conditions that favour economic growth (such as availability of infrastructure, presence of formidable human capital, durable climate for investment etc.) stands out in the way post-reform growth pans out. Atul Kohli (2006) discusses this very issue while analysing divergent growth trends in Indian states. Likewise, I believe that it can be assumed that this is true for national economies as well. A further proof of this could be a greater success that East Asian countries have been able to achieve, unlike, for example, India. The fact that South Korea and Taiwan in particular had well-established infrastructure and large state power played a role in ensuring high growth rates through open, export-oriented economies. In contrast, in India, fragmented power structures and differing demands of varied interest-groups have led to slower efforts to rapidly integrate into the global economy. Thus, we can see that the presence of favourable ‘initial conditions’ and a pro-business state are equally important in determining the implementation of these policies.

Thus, one of the cruel ironies was that these programmes of economic stabilization could not necessarily lead to political stabilization, moreover, they led to just the opposite result - increased political instability.

References Cited:

Dunham, David and Jayasuriya, Sirisa. (2001) ‘Liberalisation and Political Decay: Sri Lanka’s Journey from a Welfare State to a Brutalised Economy’. Netherlands: Institute of Social Studies.

Ghosh, Jayati. (1998) ‘Liberalization Debates’ in Terrence J. Byers (ed.) The Indian Economy: Major Debates Since Independence , Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 295-335.

Kohli, Atul. (2006) ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005: Part 1: The 1980s’ , Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 13. pp. 1251-1259

Kohli, Atul. (2006) ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005: Part 1: The 1990s and Beyond’ , Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 14. pp. 1361-1370

Corbridge, Stuart and Harriss, John. (2000) Reinventing India: Liberalization, Hindu Nationalism and Popular Democracy, Cambridge: Polity Press

Herring, Ronald. (1987) ‘Economic Liberalisation Policies in Sri Lanka: International Pressures, Constraints and Supports’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 22, No. 8, pp. 325-333

The Taiwan Question & Sino-American Relations

In May 2021, during a trip to China to promote the new installation in the Fast & Furious movie franchise, famous American actor and professional wrestler John Cena got himself in a heap of trouble when he said, during an interview on Taiwanese TV, that Taiwan would be “the first country to watch Fast & Furious 9”. More precisely, Cena received backlash from China due to his comments, which led to him apologizing to the Middle Empire in a short video during which the former professional wrestler underlined his “love and respect” for China and its population, all in Mandarin. Of course, it did not take very long for this event to cross the entire world, becoming a source of jokes and pleasantries on the internet through various memes.

Now, why exactly am I talking about this particular news topic? Simply because this event, through all its layers of silliness, perfectly summarizes the difficult case of Taiwan, as well as the current state of Sino-U.S. relations. Indeed, objectively speaking, Taiwan does fulfill the four criteria for statehood under international law defined in the first article of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933) – a permanent population, a defined territory, a government, and the capacity to establish foreign relations with other states. In addition, it has its own flag, its own national emblem, and its own national anthem. However, Taiwan's statehood is also frequently questioned, notably by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which considers Taiwan as a part of its territory in accordance with its “One China Policy”.

In the past year, the topic of Taiwan regained in importance around the world as the PRC adopted a more aggressive and expansionist approach to its foreign policy and began a military build-up along its borders with Taiwan, raising concerns of a possible Chinese invasion. In the meantime, the United States of America, considered by many to be Taiwan's greatest ally and whose relations with China have been at an all-time low over the past few years, got involved in this situation with the goal of assisting Taipei in the event of an invasion and convincing Beijing to reconsider its plans. In front of such a complex situation, one can wonder, for instance, why and how did this all happen and and whether it could have provoked an armed conflict between the U.S. and China. These questions, and perhaps many more, will be answered in the following article.

Historical Context

To fully understand the case at hand, it is necessary to go back in time. Over the course of history, the island of Taiwan has changed hands repeatedly – from the Dutch to the Spanish, to the Chinese and finally to the Japanese, who lost it back to China after the Second World War. It is important to note that this was not the same China as today – it was in fact its pre-communist version, the Republic of China (ROC), led by Chiang Kai-shek. At this moment in time, the ROC was torn by a civil war opposing the regime in place with communist insurgents led by a man named Mao Zedong, who eventually won the war. In the face of defeat, Chiang and his troops fled to Taiwan, where they proclaimed the Republic of China in exile while Mao, after coming into power, proclaimed the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Both of them claimed sovereignty on all of China, but if most states and organizations recognized Taiwan as the “real” China at first, the tide eventually turned in the PRC’s favor as a growing number of states began to recognize Beijing’s sovereignty over China, including the United States in the late 1970s.

The One-China Policy & Taiwanese Independence

There are essentially two different visions of Taiwan. In one, Taiwan is an independent country, and in the other, Taiwan is a province of China, which is the official policy of the Chinese government regarding the island. To further elaborate, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) considers that Taiwan is a distant Chinese territory that shall be reattached to China one day under what is called the “One-China Policy”.

XINHUA

The One-China Policy is essentially a belief whose roots are linked to the fact that China, over the course of history, separated and reunited itself multiple times. In fact, the CCP considers that China’s territory still is not complete to this day as some parts of its former land are either part of another state (such as the Kashmir region in India) or autonomous, in the latter case it is Taiwan. Therefore, the main goal behind the One-China Policy is to regain these contested lands to one day make China truly united again.

Interestingly, a major part of the Sino-Taiwan dispute is linked to the fact that Taipei and Beijing have two different and conflicting perceptions of Taiwan. In fact, the tensions between the two actors started evolving to their current state following the election (and subsequent re-election) of Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen in 2016, known for being a strong advocate for Taiwanese independence – which goes against everything the One-China Policy stands for. Therefore, over the last two years, the RPC has more than doubled its military presence near the island, wishing to deter Taipei from seeking its independence and even going as far as threatening the use of “drastic measures” in the advent of this scenario.

The U.S. Role

As mentioned earlier, this dispute is not solely between Taiwan and China, as there is another actor involved – the United States of America. Of course, one may wonder why exactly the U.S. is involved, considering that it is after all a dispute between two Asian countries. Simply put, it is because it is in their best interests to do so, and for two reasons. First, as previously mentioned, although the U.S. government does not formally recognize Taiwan as an independent state (doing so would prevent Washington from having diplomatic relations with the RPC), they still maintain some relations with Taipei, thanks in part to the existence of the Taiwan Relations Act from 1979. Such relations include the provision of military equipment and training to the Taiwanese Armed Forces to safeguard the island. And while the Taiwan Relations Act does not necessarily guarantee an American military intervention in the advent of a Chinese invasion of Taipei, it would not be surprising to see the U.S intervene in this scenario, as they play a major role in Taiwan’s defense.

Second, in addition to Sino-American relations currently being at a historically low point, many political scientists argue that Beijing and Washington’s competition for the ranking of superpower could drive them towards what is commonly known amongst experts as a Thucydides’ Trap. Named after famous Greek historian Thucydides who first observed this phenomenon in his account of the Peloponnesian War, the Thucydides’ Trap typically occurs when a rising power (in this case, China) threatens to remove the dominating power (in this case, the U.S) from its throne as superpower, potentially resulting in a preventive war between the two countries. Many Thucycides’ Traps have been observed throughout history, most notably between the U.S and the USSR during the Cold War, but not all of them have resulted in a conflict. Indeed, as political scientist Brandon K. Yoder pointed out in an article on the matter, a conflict may occur between the two states if the rising power has hostile intentions and therefore “takes overtly non-cooperative, “revisionist” actions”, i.e., actions that go completely against everything the current power stands for. Would Taiwan be the straw that broke the camel’s back in that regard? On paper, it could certainly be the case. However, as it has been proven time and time again, theories do not always work out when applied in the real world.

Conclusion

As pointed out in this article, the Taiwan situation is an extremely complex one that greatly affects the already strained relations between Beijing and Washington. However, it is hard to say for the moment if this will necessarily provoke an armed conflict between the two states. Indeed, while it is true that the tensions are extremely high in that regard, the Chinese and U.S. economies are very much codependent, and both countries still cooperate on topics such as the environment. In addition, one could argue that the U.S. seems to be prioritizing a hedging strategy over armed conflict to contain China’s power, as evidenced by the recent return of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) – an association of states whose goal is to contain Beijing’s rise and of which the U.S is a member. However, as it has been proven many times in the past, international politics are extremely unpredictable, and everything can change in a heartbeat.

Reimagining India's Healthcare Sector Post-Pandemic

In light of the pandemic, India needs to reimagine its healthcare sector. With India ranking 57th in the Global Health Security Index, which measures countries' preparedness and ability to handle the pandemic crisis, it is essential to consider a wider discussion and proposal for a paradigm shift in the infrastructure of healthcare services in India. According to the National Health Profile data, public healthcare services in India, especially in the last decade, have been diminishing, with only 1.29% of the country's GDP in 2019-20 dedicated to public healthcare services. Dismally, India's public expenditure on health is reducing to amounts lower than many countries classified as the 'poorest' globally.

Major Issues Faced During the Pandemic

One of the major healthcare issues that have cropped up during the pandemic is the unavailability of basic infrastructure, where India has 8.5 hospital beds per 10,000 citizens, one doctor for every 1,445 citizens, and 1.7 nurses per 1,000 people, with all of the figures being less than the prescribed limits by World Health Organisation. In addition to the lack of ventilators in hospitals, diagnostic labs' limited availability has led to slow testing rates. There has also been an unequal distribution of workforce practices, with most of the personnel being employed in tier-I or tier-II cities, leading to understaffing problems in rural areas.

Even 2004's Integrated Disease Surveillance Program, one of the major National Health Programme under National Health Mission, for maintaining a decentralised laboratory-based surveillance system to monitor disease trends and to detect and respond to outbreaks in early rising phase, is grappling with lack of personnel and resources as well as struggling to cooperate with the district health systems across states for data collection. In addition to these problems, private healthcare providers, accounting for almost 70% of healthcare provisioning in India — holding 62% of the total hospital beds and ICU beds and 56% of the ventilators — have been offering their services at a much lesser rate than the public hospitals by reportedly denying treatments to the poor as seen in Bihar, and overcharging patients with rates as high as one lakh rupees per day in cities like Mumbai. Regarding the economic policies adopted for India's healthcare system, there is a misbalance in its expenditure on preventative care with only 7% being spent on it, according to the data of the Financial Year 2017. Even in the field of foreign trade, India imports almost 70% of its Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients from China — ultimately creating huge dependence on other nations rather than being self-sufficient — despite being known as the "pharmacy of the world" and globally having the third-largest pharmaceutical industry in the world by volume.

Long-term Measures for a Reformed Health Sector

In light of these issues, India needs to revisit its health policy, take lessons from the pandemic, and hopefully shift to a preventative healthcare economy to tackle any such future crisis. There is a definite need for increased public spending, for which health budgets need to be revised so that India's spending can inch closer to the global average of 6%. States such as Kerala attest to the efficiency of strong public health systems, which have been able to control the adversities of COVID-19 through outreach-based public health strategies and proactive social engagement. A separate Disaster Management Budget for increasing the number of beds and physicians, medical equipment, medicines, and care packages will contribute to successful prevention and cure in the long run. While foreign investments in medical education may lead to positive outcomes, the heavy dependence on other countries for APIs and drugs should be minimised. It should be used as an opportunity to mitigate India's supply of raw materials through mutually beneficial partnerships.

Increasing public spending along with active involvement of community doctors, Panchayat representatives, social healthcare workers, community volunteers, civil society groups, and women's groups will help in creating a robust mechanism for ensuring not just the implementation of government schemes and programs but also in directing efforts towards awareness campaigns, facilitating entitlements for vulnerable and marginalised groups, ensuring delivery of services, and providing local insights for health planning from below. Community healthcare professionals working in tandem with public health staff need to be strengthened in their capacities through better access to basic medical tools, equipment, resources, funding, research, and training.

Additionally, there needs to be a greater emphasis on preventative care in primary and secondary sectors. It has been noted that Primary Healthcare Centres are handling all measures needed for epidemic control, such as testing or detecting cases. However, currently, there is a downward trend in the proportion of the Union health budget allocated for the National Health Mission, which is focused on supporting primary and secondary health care, reporting a cut from 56% in 2018-19 to 49% in 2020-21. Optimum spending in this direction could mean expanding the network of Health and Wellness Centres within the Ayushmaan Bharat program as centres for spreading awareness, disease prevention, and community level monitoring.

Regarding the private sector, there needs to be a legal framework in place to ensure future cooperation between the government and private players. These definite legal frameworks should be such that they focus on the duties and social obligations over private healthcare providers' commercial interests, especially in times of emergency. While states such as Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh overtook private hospitals for providing COVID-19 care, long term cooperation for providing free services to the poor and implementing public health schemes need legal provisions for avoiding the drawbacks faced during this pandemic.

Way Forward

This marks the appropriate time for bringing in health system reforms in India by focusing on public health services, increased public spending, active social and community engagement, and regulated private sector services, for turning these dreary times into an optimistic opportunity for a vigorous healthcare system. It would also help ensure one's rights to affordable, accessible, and quality healthcare by employing inputs from all key stakeholders and building solidarities across differences to bridge inequalities.

References

https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf

http://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/8603321691572511495.pdf

https://thebastion.co.in/covid-19/disease-surveillance-in-india-from-sars-cov-to-covid-19/

Edited by Hiba Arrame

Blame the Government: How State-Sponsored Inequality Made the Sahara-Sahel a Battleground

The Sahara-Sahel is home to some of the lowest-income countries on Earth. Famines are recurrent, food insecurity is widespread, and poverty is the daily bread of many individuals. Nevertheless, what has attracted international attention during the last decade is the growing power of armed groups such as Boko Haram, MNLA, and AQIM. They have managed to put states up against the ropes. They have turned this turbulent region into a conflict zone between the state and armed groups, and these latter against one another. These violent non-state actors pose a threat not only to the country but also to individuals: terrorist attacks and warfare hinder human development. And violent conflict destroys and prevents economic growth in an already impoverished area. At the same time, the Sahara-Sahel has become a vital hub for the international trafficking of drugs, weapons, and human beings.

MINUSMA Blue Helmets in Mali. Source: French Delegation to the UN

Many factors have been put forward to explain the explosion of violence in the region, from colonial borders to failed governments. However, its roots lie elsewhere. Systemic marginalization and neopatrimonialism in politics are the ones to blame. States in the region have created the perfect conditions for the flourishing of a lucrative criminal economy and armed groups' appearance. This article will analyze the horrible politics of the Sahara-Sahel and the violence and crime they have created. We will then look into the cases of some countries. We will finally explore ways to make individuals in the Sahara-Sahel more secure and freer.

States Rotting from the Inside